Why Plyometrics are Good for Athletes

Plyometric training involves the usage of jumps, hops, bounds, and/or skips and should not be confused with ballistic training. This form of training is governed by the stretch-shortening cycle, otherwise known as the reversible action of muscles. Plyometric activities can be separated into two categories depending upon the duration of the ground contact time: 1) fast plyometric movements (Less than 250 milliseconds); and 2) slow plyometric activities (more than 251 ms).

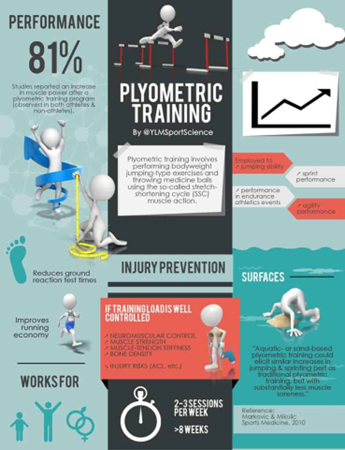

This training modality appears to be very effective for improving athleticism in both youth and adult populations. Moreover, both land- and aquatic-based plyometric training appears to be a potent stimulus for improving athletic qualities. As plyometric activities are highly coordinated and skilful movements, they should be coached with full care and attention by qualified personnel. Lastly, though training volume is relatively easy to measure, training intensity is far more complex due to the individual variability of each athlete.

What is Plyometric Training?

Plyometric training, otherwise referred to as ‘plyometrics’ or ‘shock training’, is a training modality which often requires athletes to jump, hop, bound and/or skip. Plyometrics should not be confused with ‘ballistic’ training, which is ultimately another word for ‘trajectory’ training. Ballistic training involves the trajectory of objects and implements (e.g. barbells and medicine balls), whereas plyometric training uses the previously mentioned movements.

Having said this, it is important to understand in some circumstances there is a degree of crossover, where some movements are considered both ballistic and plyometric. Ultimately the differing factor between the two is that plyometric training typically involves rapid reactive contacts with a surface (e.g. foot contacts during sprinting), whilst ballistic training involves the trajectory of objects/implements.

Plyometric training takes advantage of a rapid cyclical muscle action known as the ‘stretch-shortening cycle (SSC)‘, whereby the muscle undergoes an eccentric contraction, followed by a transitional period prior to the concentric contraction

The picture below shows an athlete’s ankle moving through the SSC sequence (eccentric, to amortization, to concentric) during a jump. Therefore, this muscle action (i.e. SSC) is often referred to as reversible action of muscles and is existent in all forms of human motion whenever a body segment changes direction.

Duration of the ground contact time

During walking, running, and jumping our feet continuously strike the ground and then leave it again in a reciprocal fashion – meaning when one foot leaves the ground, the other is quick to contact it. The time period in which the foot is in contact with the ground is known as the ‘ground contact time’ (GCT). During sprinting, for example, the foot GCT can be anywhere between 80-90 ms.

Plyometric movements which are synonymous with the SSC, are classified as either ‘slow’ or ‘fast’ plyometric activities.

• Slow plyometric exercise = GCT more than 0.251 seconds

• Fast plyometric exercise = GCT less than 0.25 seconds

Why is Plyometric Training important for sport?

As the SSC exists in all forms of human motion from changing direction in rugby to jumping in basketball, and even sprinting in the 100 m, it becomes obvious that all of these movements can be deemed as plyometric activities. As all these movements are classified as plyometric movements/activities/exercises, its importance in sport suddenly becomes transparent.

With the growing interest in plyometric training, many researchers have attempted to identify the potency of this training modality for improving athletic performance. To date, plyometric training has been shown to improve the following physical qualities in both youth and adult populations:

Strength

Speed

Power

Change of Direction Speed

Balance

Jumping

Throwing

Bone density

Furthermore, even aquatic plyometrics have been shown to improve:

Speed

Change of Direction Speed

Balance

Jumping

How does Plyometric Training improve performance?

Though seemingly simple, this is, in fact, a difficult, and very exhaustive, question to answer. As plyometric training is governed by the SSC, the question “how does plyometric training improve performance” is perhaps better referred to as “how do changes to the SSC improve performance?”

Many neurophysiological mechanisms have been considered to underpin and explain the impact of plyometric training on the SSC. Most of which include:

Improved storage and utilization of elastic strain energy

Increased active muscle working range.

Enhanced involuntary nervous reflexes.

Enhanced length-tension characteristics

Increased muscular pre-activity.

Enhanced motor coordination

Improving these qualities will likely lead to an increase in leg stiffness during contact with the ground, and also force production during the concentric contraction. Increases in both leg stiffness and force production will likely lead to improvements in athletic performance.

Issues with Plyometric Training

Though plyometric training is a very potent training modality for improving athletic performance, there are several important issues practitioners must fully understand and take into consideration before they attempt to deliver any form of training prescription.

Plyometrics are highly coordinated and skilful movements

Plyometric activities require athletes to produce high levels of force during very fast movements. They also demand the athletes to produce this force during very short timeframes. Perhaps the best example of this is sprinting. Maximal speed sprinting demands that the athlete moves their body and limbs at the very pinnacle of their ability – making it an extremely fast movement.

As a result, plyometrics are not typically seen as just exercises or drills, but more as complex ‘movement skills’ due to their high complexity. Understanding this is vital and highlights how highly-coordinated these movements are, and why they require a large amount of attention and coaching if optimal, yet safe, performance gains are to be made.

The intensity of plyometrics is difficult to measure

Arguably, volume of plyometric training is relatively easy to measure and prescribe and is typically done so by counting the number of ground contacts per session, otherwise referred to as simply ‘contacts’. However, measuring and prescribing plyometric intensity is far more complex. To accurately measure plyometric intensity, the following components must be taken into consideration:

Speed of movement

Amplitude of movement

Points of contact (i.e. unilateral or bilateral)

Body mass

Technical competencies

Strain yielding competencies.

Injury Risk

Plyometric exercises, which involve explosive movements like jumping and bounding, can be highly effective for improving athletic performance. However, they also come with certain risks, especially related to the impact forces involved. Here are some common problems associated with impact in plyometrics:

Injury Risk: High-impact plyometric exercises can increase the risk of injuries such as sprains, strains, and stress fractures. This is particularly true if proper technique and progression are not followed

Joint Stress: The repetitive jumping and landing can put significant stress on the joints, particularly the knees and ankles. Over time, this can lead to joint pain or even long-term damage.

Muscle Fatigue: Plyometric exercises are demanding on the muscles, and overuse can lead to muscle fatigue and soreness. This can affect performance and increase the risk of injury.

Improper Progression: Jumping into high-intensity plyometrics without proper preparation can lead to injuries. It's important to start with low-intensity exercises and gradually progress to more intense ones

Volume Management: Doing too many plyometric exercises without adequate rest can lead to overuse injuries. It's crucial to manage the volume and intensity of these exercises to avoid excessive stress on the body

To minimize these risks, it's important to follow proper training protocols, including a thorough warm-up, focusing on technique, and ensuring adequate rest and recovery

To provide just one example, let’s take a quick look at body mass. If two athletes perform a drop-jump from a 30 cm box, but athlete A is 60 kg and athlete B is 80 kg, then athlete B has to absorb and re-apply more force than athlete A simply because of their weight.